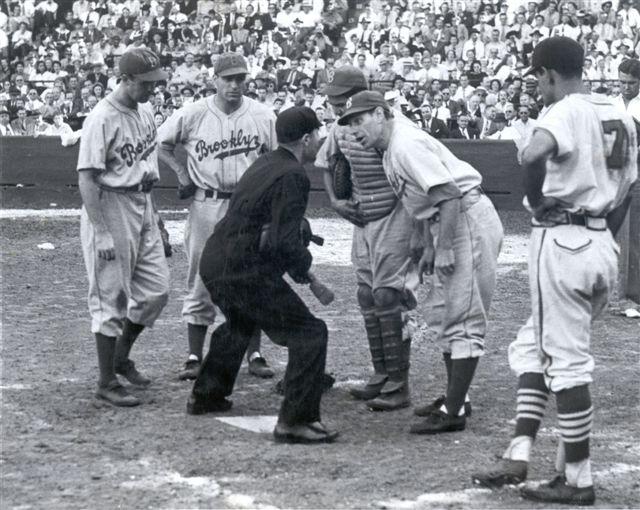

Umpires ejected manger Leo Durocher from 95 baseball games. No wonder he was dubbed “Leo the Lip.” He feuded with the press, baseball commissioners, and anyone else who crossed him. His teams won three pennants and a World Series, and they didn’t do that by being nice.

The saying “Nice guys finish last” comes from Durocher. 29 years after he said it, he made it the title of his autobiography.

I’ve spent a lifetime wanting Durocher to be wrong. Hoping he was wrong. The older I get, the more I think The Lip was onto something.

Nice people don’t win.

They don’t want to offend anyone, and shy away from conflict. Nice people don’t want to hurt your feelings when you’ve made a mistake. They wish everyone would get along. They hope uncomfortable tension will naturally diffuse.

But hope is not a strategy and life is messy. Few if any accomplishments happen without conflict and tension. We get better when we deal with it head on. We get better when we get honest feedback about the gap between our intent and our impact. The gap between our performance and our potential.

So sharpen those elbows. It’s a dog-eat-dog world. If you’re not looking out for number one, no one else will.

Not so fast.

Nice people might not win, but who wants to live in a world of back-stabbing incivility? Who wants to always question their teammates’ motives? No one sleeps well with one eye open.

So what’s the alternative?

Farnam Street‘s Shane Parrish, host of The Knowledge Project podcast, draws a distinction between “Nice” and “Kind” feedback. A nice person avoids a potentially uncomfortable conversation after a meeting. A kind person lets you know how you can get better. A kind person feels an obligation to help you, even if that means stepping into the tension.

My friend Joseph Currier, Ph.D. has long evangelized the Team Rule, the idea that we have an obligation to give our partners feedback, and we have an obligation to deliver and receive that feedback in a caring spirit. People who are too nice don’t lean into this process. It only works, though, if the people who do lean in, do so with kindness.

The good news: this isn’t just some kumbaya corporate speak. Evolution tells us that kind people finish first. The fittest tribes survived by dividing responsibilities and working together to fend off predators. And the best teams run on trust and collaboration and a persistent desire to get better, both as individuals and a unit. That doesn’t happen when people are too nice, and it doesn’t happen when sharp elbows are out.

At an early age, we’re told we can grow up to be anything we want. This world would be a better place if stopped trying to be nice and, instead, we chose to be kind.