In the closing minute of the Super Bowl, Pete Carroll had a decision to make. Hand the ball off to Marshawn Lynch, the best short-yardage back in the league, or spring a surprise on the Patriots? He opted for the latter. Malcolm Butler picked off Russell Wilson’s quick slant, the Patriots hoisted the Lombardi trophy, and Carroll invited years of second-guessing and blame.

Why didn’t he give the ball to Beast Mode? They were on the one yard line!

Here’s the thing. If the play had worked, many of those second-guessers would be calling Carroll a genius. Eleven Patriot defenders and 100 million viewers expected Lynch between the tackles. The Patriots had put in their goal line defense to stuff the run. Carroll said he intended to run on third down if the second down play didn’t work. He hadn’t counted on an interception. Or, better said, he put low odds on that scenario, which was right. There had been 65 passes attempted from the one-yard line that year. Zero had been intercepted. A fumble is actually more likely (there had been two in 200 attempts).

Carroll made a bet that didn’t pay off.*

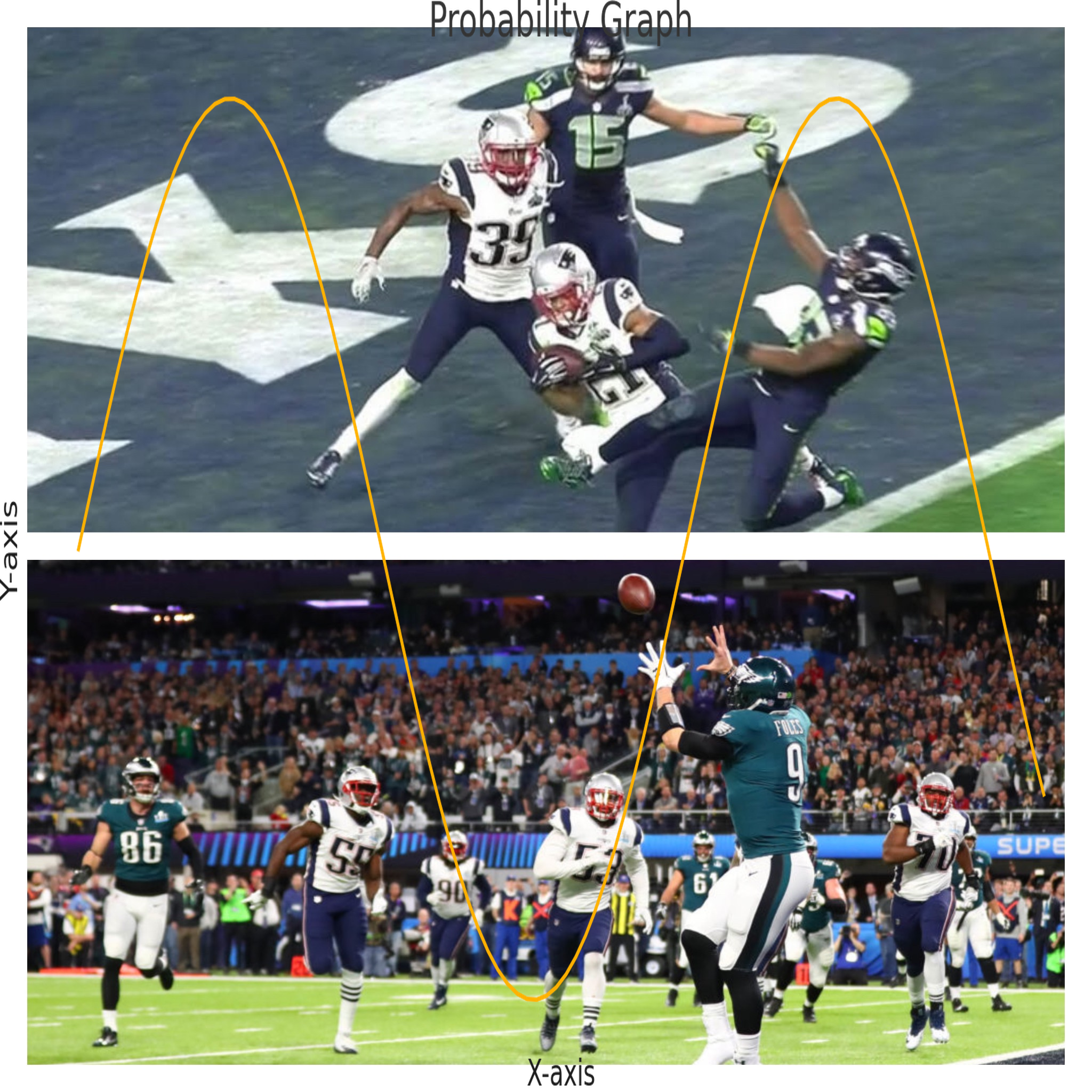

Three years later, on a 4th and one at the goal line, Eagles coach Doug Pedersen called a trick play known as The Philly Special. NFL Films described it as “a play that the Eagles had never called before, run on 4th down by an undrafted rookie running back pitching the football to a third-string tight end who had never attempted an NFL pass before, throwing to a backup quarterback who had never caught an NFL (or college) pass before, on the biggest stage for football.”

Nick Foles caught the pass, the Eagles defeated the Patriots, and the talking heads praised Pedersen. It was a brilliant play design and took guts to call in the Super Bowl. It showed the bond between Pedersen and Foles, who agreed on the play in a moment captured on video. A statue outside of Lincoln Financial field memorializes this play call. If it hadn’t worked, people would be saying, “Why get cute at that point in the game?” “What was Pedersen thinking?” “Do you really want to get talked into a call by your back-up quarterback?”

We have a hindsight bias— the outcome reshapes how we think about the decision. But our reaction to these scenarios exposes another problem: We think in deterministic terms, even though we live in a probabilistic world. We assume there’s a right and a wrong answer. This age of uncertainty, this age of iterative learning, requires that we understand the probabilistic nature of the world.

It means we can do everything “right” and still end up with a less than optimal outcome. It also means we can get lucky when we hit on 18. It means someone wins the Powerball even when statisticians consider the lottery a tax on people who disregard math. It means the slant pass might have given the Patriots the best chance to win and the Philly Special might not have been the optimal play call. We’ll never know. As an Eagle fan, I’m glad it worked out the way it did, and I like to tell the story as one of courage, brilliant deception, and trust between a coach and his team.

My Journey from Deterministic to Probabilistic Thinking

It took me a long time to understand the difference between probabilistic and deterministic thinking. I’d agonize over decisions and feared making mistakes. I’d beat myself up when things didn’t turn out the way I’d hoped. I’d want to know who made a decision that didn’t work out. In a deterministic world, we blame. We blame ourselves, and we blame others when things don’t go the way we want.

When you see the world through a probabilistic lens, you start to think in bets. You realize that an environment of blame gums up decision-making. That people will look for near certainty before moving forward and will not own the outcome for fear of reprisal. They’ll dwell in the past, applying hindsight bias to any decision that didn’t work out.

In a probabilistic world, you stop blaming yourself for failures and realize that the so-called failure just disproved a hypothesis. You learned something. Or maybe you were just unlucky. You find two-way doors and stress a lot less about decisions. You take action. You test your hypotheses and back out when they don’t pan out. Blame gets replaced with learning.

For a while, I confused a hypothesis with an educated guess. That’s how people think of it in a deterministic world. “Did I guess right?” Here’s a definition built for a probabilistic world: A hypothesis is a tentative explanation for something that you set out to prove or disprove. It’s a bet you’re willing to make. In today’s world, we’d be well served to think of many of our decisions in those terms.

Pete Carroll might have made a bad bet. It’s hard to say. But it’s so much healthier to understand he was weighing probabilities. For Seahawk fans, it’s too bad the interception turned a two-way door into a one-way exit. That was a very improbable outcome.

And for Eagles fans like me, all hail the Philly Special!

Fly Eagles Fly!