Every so often, you meet a person who exists on a different plane– someone who rises above day-to-day struggles and reminds you what really matters through both words and actions.

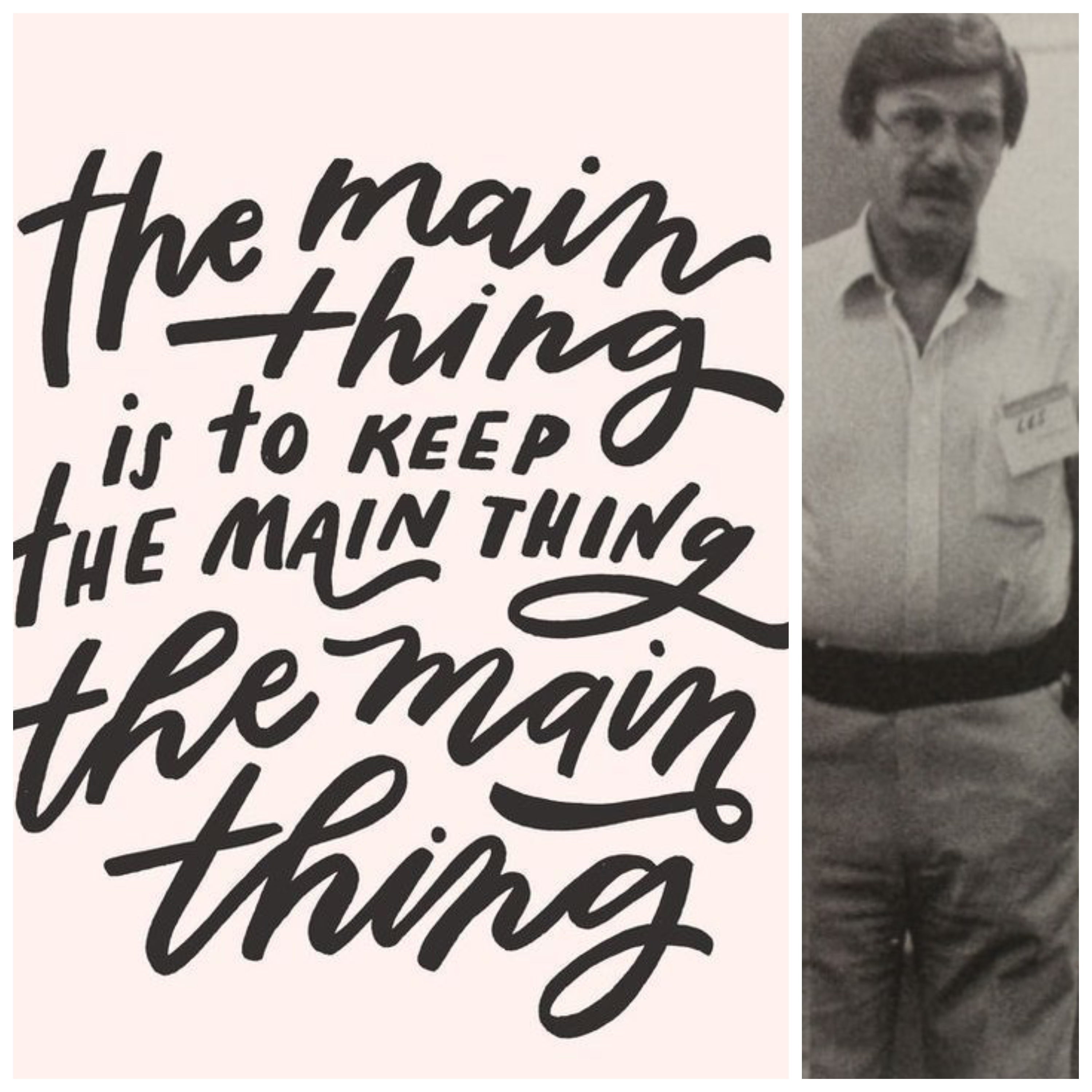

Dr. Les Frankfurt was just such a person.

I met Les in a conference room almost 25 years ago. Several of us were convening to hammer out priorities for the coming year. Les positioned himself in the back of the room. The discussion was charged, everyone competing to have their opinion heard. Les came across as meek, almost blending into the furniture. I suspect most of us forgot he was there.

We weren’t getting very far and, toward the end of our scheduled hour, we heard a soft-spoken voice with a Hungarian accent. “Would it be okay if I asked a question?”

All eyes turned to Dr. Les. “Sure,” said the guy running the meeting.

“I hear you talking about a lot of things. But what is the main thing?”

“What?”

“You’re talking about a lot of things. But what’s the main thing?”

This prompted another round of debate, everyone digging heels in and lobbying for his or her position. “We need to focus on new customers.” “No, we need to keep the customers we have.” “We need to align compensation.” “Technology; we need better technology.” “No, it’s process.” “I get all that, but we need better metrics. What gets measured gets done.”

“So, I don’t think you understand,” Les said. “I want you tell me: What is the Main Thing?”

More debate. More raised voices. The Type As were there to win.

He interjected one more time in his quiet, but persistent voice. “These sound like strategies and tactics. Maybe they are the Main Thing. But I don’t think tactics are The Main Thing.”

We all arrived there within a few seconds of one another.

“People,” someone said.

“Relationships,” said someone else.

“Trust.”

“How we care about each other.”

Dr. Les smiled. After a brief pause, he said, “You must always keep the Main Thing the Main Thing.”

We let this sink in for a moment, and then Les said, “The Main Thing is to keep the Main Thing the Main Thing.” His voice was quiet, but far from meek. We had all stopped talking and just listened.

We thought about what he said. We’ve thought about it for 25 years.

#

On a gray January afternoon in 2018, I learned that Dr. Les Frankfurt had passed away.

The world got a little colder. A little darker.

To know Les was to love him. He was a slight man who wouldn’t reveal his age, even to his closest friends. We all speculated he was pushing 90. He still worked with a number of us and still had a magical ability to make you look inward to discover what was most important. He was a psychologist who had helped hundreds of people sort out their past so they could better move forward. He had some personal experience in this regard.

He was very smart but kept it simple. That conference room interaction wasn’t a one-off. Les reminded everyone he worked with and just about everyone he met to keep the Main Thing the Main Thing.

I later learned that Stephen Covey used that same expression. It was deflating to think that it hadn’t come from Les, but is anything really original? Besides, more than talk about the Main Thing, Les had lived it. He made the saying his own.

I never had a one-on-one session with him. My memories were more of hallway encounters where he would pay me or a colleague some compliment. He had lived in the US for seven decades but that thick, Hungarian accent never left him.

“I am hearing very good things about you,” he would say.

“Thanks, Dr. Les,” would come the reply. “Good to hear I’ve fooled some people.”

“I am not joking. You need to learn to say ‘Thank You.’ These people are singing your praises. You need to know this.”

“I know. I know. I’m not great at taking a compliment. Thank you, Les. That’s very kind of you to share. It makes me feel great.”

“Let me tell you a secret,” he would say, leaning in a bit. “I don’t share these things to make you feel good. I share them to make me feel good.” He would then give a legendary, Dr. Les hug, one that lasted just a little longer than comfortable. One where you wanted to unclench, but you didn’t want to offend Dr. Les; after all, you knew he was giving you that hug because it made him feel good.

#

The day after I learned there would be no more hugs, I resolved to call his son to express my condolences and to let him know about the indelible mark Les had left on our company. It’s not a call I wanted to make. I didn’t know his son, and he would be grieving. But it was an important call and I thought it would mean a lot not because I had particular insight, but because I happened to be the president of Allegis Group, and Les had worked with us for almost 25 years. That week, making that call felt like The Main Thing.

Still, I procrastinated. I waited until Friday afternoon telling myself I would not leave the office until I’d completed this mission. Truth be told, I was relieved when the phone rang a few times and went into voicemail. I told Les’s son how sorry I was to hear about his dad, and I mentioned how his dad had been a force that we would never forget. How he taught so many of us to “Keep the Main Thing the Main Thing.” I wanted him to know how much his dad was loved and how many people he impacted.

That night, his son called me back to let me know how much these words had meant. I wanted to break out my bad Hungarian accent and tell him that I called not to make him feel better, but to make me feel better. I didn’t. Not at that solemn moment.

After a pause, he asked if I would speak at his dad’s service on Sunday morning.

A lot went through my mind. I was headed to Atlanta on Sunday for some early Monday meetings; the Eagles were playing the Vikings in the NFC Championship game, and I had rearranged my flight to get to Atlanta in time to watch. Oh, and my son had a basketball game in the morning. Sunday was not a good day.

“What time’s the service?” I asked, secretly hoping it would conflict with my plans.

“9:30,” he said. I didn’t fly out until noon. Plenty of time. And I could miss one basketball game. And then my next round of objections surfaced. I thought about my relationship with Les. I had a deep admiration for him, but we weren’t that close. I wasn’t worthy of delivering a eulogy at his service and had called more because of my position than my direct relationship. Surely others would better honor his legacy.

I dipped my toe in that water. “Les was the best,” I said. “And I’m so honored that you would ask me. I’m sure there are others, though, that were closer to Les.”

“It would mean a lot to me and the family if you would share a few words,” he said.

This was not a debate I should be having. “Let me see if I can swing it. I’ll follow up with you either way.”

When I hung up, I was thinking about graceful ways to say no. It wouldn’t have been hard, and I’d likely never see his family again. Besides, whoever took my place would do a great job. They could speak at a deeper, more personal level.

#

I love, and I hate funerals.

I love that you get to hear about someone’s best qualities and understand the difference they made in the world. I love that people come together to celebrate a life and to share in grief. I love the spirit of community. And I love the smack in the face that comes from realizing what really matters. Eulogy values over resume values. Is there a better place to reflect on why we’re here? A better place to contemplate The Main Thing?

On the flip side, I hate that the person in the casket maybe didn’t know about the impact she’d made. That the people at the viewing share stories that they might not have shared with the deceased. I hate wondering if the person died worrying about how others might grieve, unaware of the outpouring of support for those most in pain. I hate the awkwardness of offering condolences to people I don’t know and making small talk a few yards from a body awaiting burial.

I talked to my wife Jen about Dr. Les’s funeral. I told her I didn’t think I wanted to go and didn’t feel worthy of speaking; I also told her I felt guilty. Conflicted.

“I get it,” she said. “Sounds inconvenient. When in doubt, always go to the funeral.”

This phrase came from a radio essay, we had heard on a road trip almost fifteen years earlier. It had stuck with us and served as a reminder to sometimes do things we don’t want to do. It’s called “Always Go to the Funeral” by Deirdre Sullivan, JD, CIPP:

_____

I believe in always going to the funeral. My father taught me that.

The first time he said it directly to me, I was 16 and trying to get out of going to calling hours for Miss Emerson, my old fifth grade math teacher. I did not want to go. My father was unequivocal. “Dee,” he said, “you’re going. Always go to the funeral. Do it for the family.”

So my dad waited outside while I went in. It was worse than I thought it would be: I was the only kid there. When the condolence line deposited me in front of Miss Emerson’s shell-shocked parents, I stammered out, “Sorry about all this,” and stalked away. But, for that deeply weird expression of sympathy delivered 20 years ago, Miss Emerson’s mother still remembers my name and always says hello with tearing eyes.

That was the first time I went un-chaperoned, but my parents had been taking us kids to funerals and calling hours as a matter of course for years. By the time I was 16, I had been to five or six funerals. I remember two things from the funeral circuit: bottomless dishes of free mints and my father saying on the ride home, “You can’t come in without going out, kids. Always go to the funeral.”

Sounds simple — when someone dies, get in your car and go to calling hours or the funeral. That, I can do. But I think a personal philosophy of going to funerals means more than that.

“Always go to the funeral” means that I have to do the right thing when I really, really don’t feel like it. I have to remind myself of it when I could make some small gesture, but I don’t really have to and I definitely don’t want to. I’m talking about those things that represent only inconvenience to me, but the world to the other guy. You know, the painfully under-attended birthday party. The hospital visit during happy hour. The Shiva call for one of my ex’s uncles. In my humdrum life, the daily battle hasn’t been good versus evil. It’s hardly so epic. Most days, my real battle is doing good versus doing nothing.

In going to funerals, I’ve come to believe that while I wait to make a grand heroic gesture, I should just stick to the small inconveniences that let me share in life’s inevitable, occasional calamity.

On a cold April night three years ago, my father died a quiet death from cancer. His funeral was on a Wednesday, middle of the workweek. I had been numb for days when, for some reason, during the funeral, I turned and looked back at the folks in the church. The memory of it still takes my breath away. The most human, powerful and humbling thing I’ve ever seen was a church at 3:00 on a Wednesday full of inconvenienced people who believe in going to the funeral.

_____

Not long before Dr. Les died, a friend of mine called on the anniversary of his dad’s passing. I told him I was sorry, and that I was also sorry that I hadn’t remembered. He shrugged that off. Said he’d been thinking about his dad’s funeral eleven years earlier. That he’d never forget seeing me walk into the New Jersey funeral home after a several hour drive from Maryland.

We hadn’t talked about that moment in the ensuing eleven years, but it proved an enduring memory. Something that “represents only inconvenience to me, but means the world to the other guy.”

I’ve missed some funerals I wish I could have attended. Sometimes, it’s not practical. But, when in doubt: Always go to the funeral.

#

I went to the funeral.

I also agreed to say a few words to honor Dr. Les. It was the least I could do if it gave his family and friends even some small comfort. I also had to get over myself. Turns out I was one of many speakers. I was not delivering the main eulogy. In fact, I was slotted to go first, and each successive speaker would be closer to Les, culminating with some words from a grandchild.

Les had lived an extraordinary life. He survived the Holocaust. His parents didn’t. Some 75 years earlier, the Nazis had experimented on him and his twin brother in a concentration camp. He witnessed atrocities that most can’t even imagine. Atrocities that I can never imagine.

A guy who had every reason to be bitter, Dr. Les proved every social media platitude ever written about mindset. Of course he would spend his life helping people sort out their past and move forward. He was like our own walking, talking, hugging Victor Frankl. You always left an interaction with Dr. Les feeling just a little bit better about yourself and about life.

No doubt that made him feel good.

Whenever anyone talked about Les, they would smile. You couldn’t help it. He radiated positivity. It would not be hard to say some nice things about this beautiful man and the beautiful life he lived. His ability to help people move forward, become a force for good in what can sometimes be a dark, unforgiving world. No one knew that better than Les.

I told the story about the first time I met Les, the meeting in which he had challenged us all to think about The Main Thing. I told this story to a hundred or so people who had gathered to pay their respects. I didn’t do the Hungarian accent, but I played up his quiet persistence. His family and friends all smiled, and I thought that I must have done a pretty good job representing their Les.

Speakers followed me, and it became clear that they had been smiling for another reason. Joseph Currier, Ph.D., his dear friend and business partner of 49 years, told stories about Les mentoring him through difficult times. He talked about Les’s vulnerability and insecurity. His love for the man. Neighbors shared how much he had meant to them. A grandson talked about having breakfast with Les almost every week and even mentioned uncomfortable hugs in the coffee shop parking lot. There must have been eight or so speakers, each one with a more intimate relationship than the last. They were funny and thoughtful and touching. And each one made mention of Dr. Les’s constant quest to help them determine their Main Thing.

Les had so tightly integrated his words and deeds. Truly a life well lived. I left that funeral wanting to be a better dad, a better husband, a better friend, a better leader, a better son, and a better brother. I wanted to be more like Les. And I left that funeral damn sure Stephen Covey had stolen the Main Thing from that quiet, persistent Hungarian!

Covey could have “begin with the end in mind.” He could have his seven habits. Not the Main Thing! The Main Thing would forever belong to Dr. Les Frankfurt. Of that I was certain.

#

Dr. Les’s advice might seem obvious or trite– a variation on: “Don’t sweat the small stuff” or “Keep your eyes on the prize.” Chicken Soup for the soul. Maybe it’s because I knew Les and can hear that accent, but The Main Thing still hits me as profound– much easier said than done and the perfect reminder when I get mired in daily struggles or just feel stuck.

Sometimes what our head dismisses, our heart understands. Les spoke the language of the heart.

So many of our challenges aren’t challenges of the intellect– they live at an emotional or maybe even spiritual level. I’ve called this newsletter The Liminal Age because so many of us are living in Between Times, having crossed over one threshold but not quite certain if and when we’ll cross the next.

Victor Turner, a Scottish anthropologist who did pioneering work on liminality, said, “The attributes of liminality or of liminal personae are necessarily ambiguous. One’s sense of identity dissolves to some extent, bringing about disorientation, but also the possibility of new perspectives.”

Said another way, the liminal is not some intellectual problem to solve– it’s a challenge of identity and emotion. Those challenges are “necessarily ambiguous” and bring about disorientation. Dr. Les got that. And as much as we can frame “The Main Thing is to keep The Main Thing the Main Thing” as a way to achieve our life goals, it’s also a recipe for managing the disorientation and anxiety that comes from living betwixt and between, our identity dissolving with some uncertain promise to re-form at some indeterminate future time.

I find Turner and other academics’ writing on liminality helpful, but fittingly it’s the examples that bring out the emotional resonance more than a carefully crafted academic definition.

I’ve watched my kids walk the high school stage and live in that weird space before college orientation, sad and excited and confused, consciously or subconsciously deciding which high-school personas to shed and what a new start might feel like. I was reminded of my own feelings some 37 years ago as I loaded my CD collection in the car, wondering what it would say about me to my new roommates. Emotions reach a fever pitch in those weeks before college drop-off. The raised voices and slammed doors have nothing to do with the towel on the floor or the question about curfew.

In “Dopesick,” a heartbreaking account of the opioid epidemic, Beth Macy titles a chapter “Liminality.” In that chapter, a woman who helps addicts find treatment says, “The moment an addict is willing to leave for treatment is as critical as it is fleeting.” She calls it the liminal phase. I haven’t been there, but can only imagine the ticking-clock, beating-heart urgency friends and family and addict must all feel. And the emotional reward for making it through that liminal phase? More liminality. Macy tells the story of too many young people whose Main Thing became chasing a high. Or, maybe worse, trying to fend of dopesickness. The moment an addict is willing to leave for treatment is that fleeting opportunity to displace those Main Thing with a new Main Thing. No wonder step one is to give yourself up to a higher power.

I can only imagine the confusion that an addict must feel and the emotional rollercoaster she must ride during 28 days of treatment, a liminal space intended to help someone shed one skin and try on another. I’ve had good friends get sober, and they’ve talked about having to find all new people to hang out with and a new set of social activities, realizing their addiction and their environment had become so intertwined. Turns out there’s no magic in 28 days. They never fully leave that liminal space, always in recovery.

While confusing and disorienting and frightening, Liminality can also hold so much promise. So much potential. In fact, almost all progress moves through the liminal. We feel it when we start a new job or when we show up for high school softball tryouts. When we hit submit on a college application or even a social media post and wait to see the response. We know that growth happens when we make it through adversity.

Writers live in that liminal space when they’ve submitted a book to their publisher. They often describe a sense of relief mixed with terror, waking from a sound sleep only to bolt upright in bed, certain that their work will meet with abject failure. We’ve all been there.

An engagement might as well be one, long, exciting liminal phase, two people having exited their single life with a proposal and ring ritual awaiting their formal formation as a couple through the reciting of vows. Is there a better feeling than young love professing their hopes and dreams to one another in front of friends and family? Aside from funerals, weddings might bring the most clarity to Dr. Les’s question about the Main Thing.

We’re constantly moving in and out of the liminal and Dr. Les’s advice, intellectually obvious, feels like the emotional foundation necessary to make it to the other side. Maybe it’s the mortar that holds the foundational bricks together. But in the midst of struggle, stuck in the liminal, it can be so hard to keep the Main Thing the Main Thing.

I’ll never forget driving out of my office parking lot on Friday, March 13, 2020 after we’d made the decision to have everyone work from home. It had been a brutal week of changing information and emotional dissonance. I felt relief that we’d made the decision, but also fear that our network wouldn’t be up to the test. I was concerned about the viability of our economy and our business in the face of this disruption and worried that the virus spread would impact people I loved. I didn’t sleep much that weekend, waiting for what Monday would bring.

Twenty thousand people logged in from home on the 16th, a tremendous relief and point of pride, but that didn’t mark the end of that liminal phase. There was still so much uncertainty. By Wednesday, I was hearing stories of our team members checking in on furloughed workers and people working around the clock to find and distribute laptops so displaced workers could still get a paycheck. I watched new communication channels form and relationship bonds strengthen. Everyone was in survival mode, but their main instinct was to help those around them. Crisis and liminality had clarified the answer to Les’s question.

His funeral had been 26 months earlier, but Dr. Les was alive and well. We were all doing our best to keep the Main Thing the Main Thing.

#

We need the emotional foundation Les championed. More than ever, we need that mortar. When we’re quick to judge, we need empathy, that reminder that everyone’s going through something. Everyone fights battles we don’t see. Everyone navigates some liminal space, hoping to emerge whole on the other side.

We’re all navigating some such space.

Whether you’re starting a new job, contemplating a change, feeling a little lost or maybe just burned out, you can feel overwhelmed by choices. Bombarded by stimuli. You can worry about all the things that might go wrong. Crushed by the ambiguity and disorientation. Maybe you’re going through a divorce or seeking treatment or dealing with an aging parent. Maybe you’re just excited about the next phase in your life. You’ve walked an actual or metaphorical stage and are readying for the next chapter.

Wherever you are, whatever you’re doing, you’d be well served to remember Victor Frankl’s comment about agency: “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

And when you’re thinking of Victor Frankl’s quote and recognizing that you have the power to respond, the power that grants you growth and freedom, I hope you hear a soft but forceful voice in your head, asking you about the Main Thing.

You might be tempted to dismiss the question. Push it aside while you get stuff done. Yeah, yeah. I know. Not recognize the awesome power and responsibility that comes with that freedom.

I hope that voice has a Hungarian accent and persists in asking you the question again and again. “But what is the Main Thing?”

After all, the Main Thing is always to keep the Main Thing the Main Thing. But first, we need to figure out what that Main Thing is.

Les had a lot of answers, but it was his question that left the most indelible mark. I smile as I write this and I know, somewhere, my smile makes Dr. Les feel good. He’s enveloping me in one of those uncomfortably long hugs.

So I channel Dr. Les, and I say to you, “But what is The Main Thing?”