A few months ago, Marc Andreessen published his Techno-Optimist Manifesto, a 5,000-word celebration of markets and technology and all the abundance they promise to bring. I nodded along with so much of what he said, but the gestalt experience left a bitter taste in my mouth.

Maybe I was reacting to his many grandiose, sweeping statements (e.g., “We believe that there is no material problem – whether created by nature or by technology – that cannot be solved with more technology.”), or maybe I didn’t like how quickly he dismissed opposing viewpoints. While I can appreciate his faith in technology and markets, suggesting that slowing down AI progress and all its life-saving potential is “some form of murder” seems a bit much.

In the end, though, it was something different. I’m an optimist who is skeptical of unbridled optimism. Utopian visions scare me. In fact, I don’t want a utopia. Life is messy, and it’s about growing and striving, trying to bridge the gap between our present and our potential.

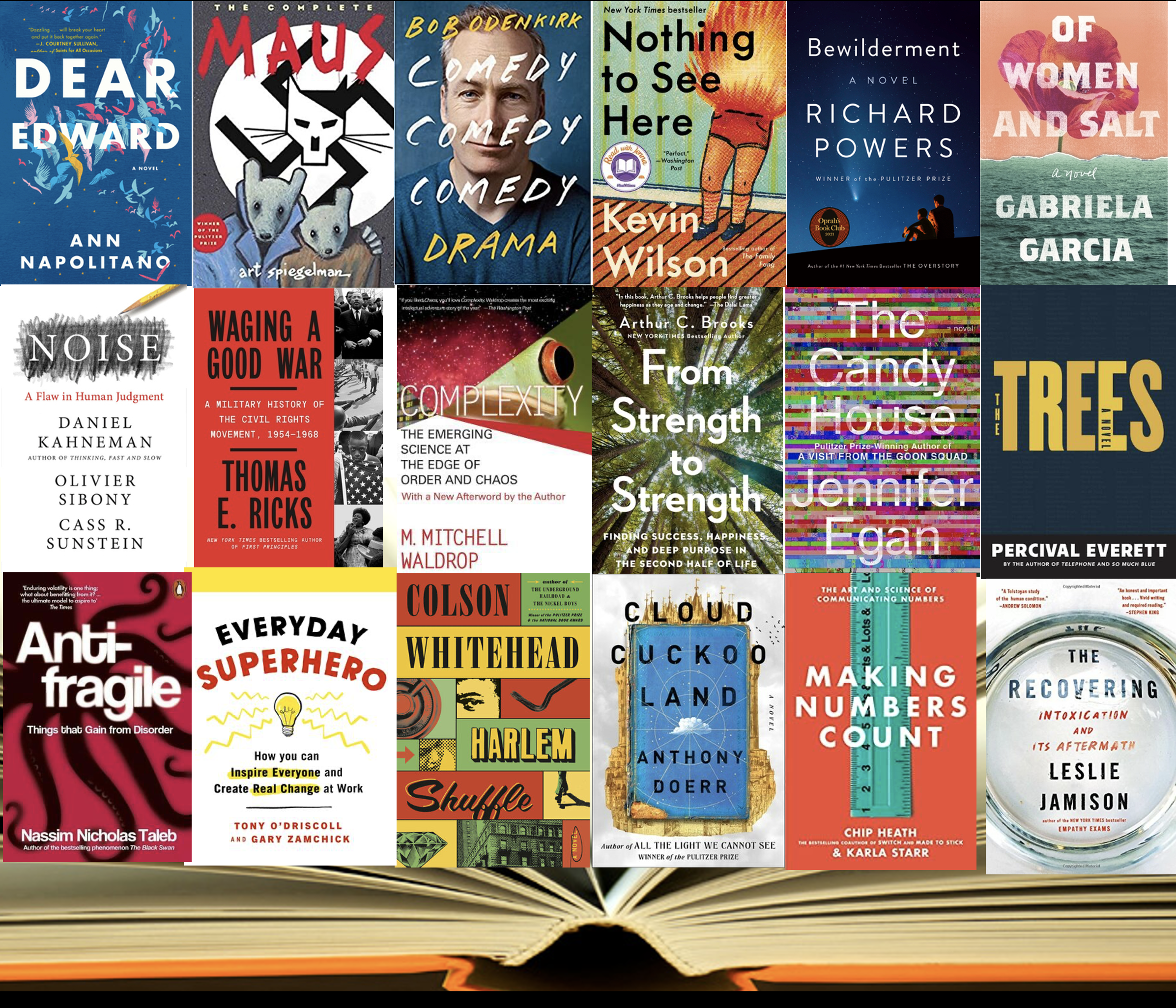

I read a lot of amazing books this past year, the best of which shed light on this conflict. These are the ten books that best helped me sit in the tension, understand dissenting views, empathize more deeply, and more fully consider what we need to do to build a brighter future. More than consider, though, they inspired me to do and be better.

And while that might sound high-minded, they had one other thing in common. They had me turning pages.

- Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver: Kingsolver channels Dickens’ David Copperfield in telling the story of Appalachian kids trying to make it through each day as a growing opioid criss bears down on them. Kingsolver masterfully highlights the tension between individual agency and broader economic and social forces. A book about institutional poverty, forgotten people, and hope, “Demon Copperhead” is that rare page turner that will stay with you on a deeper emotional level. It had me seeking out Kingsolver podcast interviews to better understand her love of Appalachia and the origins of this novel. While the themes sound heavy, Kingsolver infuses so much humanity into the characters and reminds us all why Dickens had people clamoring for the next issue of his serially released novels. My favorite read of 2023.

2. The Best Minds by Jonathan Rosen: Heartbreaking story of a brilliant young man diagnosed with schizophrenia, who commits an unspeakable act. What could have been– maybe even should have been. Part memoir, part deep-dive into our highly politicized, often wrong-headed attempts to treat mental illness, “The Best Minds” blends beautiful writing, emotionally rich story-telling, and deeply researched subject matter. Rosen exposes the folly of well-meaning attempts to shift to community-based housing for people with mental illnesses, taking on Ken Kesey’s anti-institutional, left wing “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” approach of the 60s/70s and Reagan’s right-wing spending cuts of the 80s. As we deal with more and more mental health challenges, Rosen serves up a cautionary tale and an explanation as to why we’re not further along. He also writes a rare memoir about a tortured friendship between two men.

3. Team of Rivals by Doris Kearns Goodwin: I’m not a Civil War buff, but I finished this book and drove to Antietam. That battle gave Lincoln the confidence to release a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation (before being officially issued on New Year’s Day 161 years ago). It’s a history book that rivals any treatise on leadership out there. Lincoln pulls his bitter political rivals into his cabinet and weighs the right thing to do against the likelihood of success at every turn. I gained a deeper appreciation for the tenuous nature of our Democracy, particularly relevant as we live through our current divide. We so desperately need strong, Lincoln-like leadership, willing to embrace dissent and rise above short-term thinking. Lincoln gives us a model and hope for a brighter future. Read it if you love history. Read it if you love the Civil War. Read it if you want to learn about Lincoln and leadership. Or read it if you just love a well-told tale.

4. Lost & Found by Kathryn Schulz: Schulz meets the woman of her dreams at a time when she’s losing her father to Alzheimer’s. She anchors her memoir in these parallel events, offering a deep exploration into our connections with one another and with the world. The writing is spectacular and the message is one of hope. She writes: “To err is to wander and wandering is the way we discover the world and lost in thought it is the also the way we discover ourselves. Being right might be gratifying but in the end it is static a mere statement. Being wrong is hard and humbling and sometimes even dangerous but in the end it is a journey and a story.” As lost as we can sometimes feel, we need to keep seeking. To be human is to question and to long for faith and meaning and that sense of purpose we find only in relation to others we love. Schulz (like Rosen) can turn a phrase like few memoir writers I’ve encountered.

5. The Fourth Turning Is Here by Neil Howes:What if we’re not on some evolutionary progression, but history and civilizations move more in seasonal cycles based on generational attitudes? Howe explores this concept and puts our current Winter into that context. If he is to be believed, things are going to get worse before they get better, but they will get better. Or at least re-set. Somehow I missed “The Fourth Turning” when it was published 25 years ago, a book in which he (and a co-author) predicted much of what we’ve experienced. Maybe it would have changed how I viewed the last decade and our increasing division. Better late than never. Howe tells us that Spring follows Winter, and we’re due for some fundamental attitudinal shifts across the globe. I finished this book with a sense of optimism, knowing that Winters end, but no less daunted by the challenge in front of us. At least Howes helps make some sense of the madness.

6. The Rabbit Hutch by Tess Gunty: Set in Vacca Vale, IN (a thinly veiled South Bend), “The Rabbit Hutch” so perfectly captures the zeitgeist of modern-day America. It’s the story of Blandina, a brilliant product of the foster care system who seems destined to waste her many talents. Gunty manages to expose the hopelessness and despair in rust belt cities while demonstrating a deep fondness and love for their soul. No mean feat. This was the first book I read in 2023 and one that stayed with me all year. A worthy winner of The National Book Award from an amazing new literary voice. I expect we’ll be reading Tess Gunty for years to come.

7. The Power Broker by Robert Caro: Early in the year, I saw a documentary (“Turn Every Page”) about the lifelong partnership between Bob Caro and his editor Bob Gottlieb. I left the theater knowing I had to finally tackle “The Power Broker.” It did not disappoint. Any time we think that the messiness of our democracy isn’t worth it, that maybe we should invest power in a single person (e.g., maybe anoint an AI Czar), we should look no further than Caro’s meticulously researched Moses’ biography. This book came out 50 years ago but is as relevant as ever. A study in the idea that power corrupts and that certain people seek power over fame or fortune. Moses shaped New York more than any elected official, building roads and parks and houses… often in exchange for more power and with no desire to make New York a city where all could live and thrive. I look at New York and cities and governments and roads and parks and bridges a little differently after reading “The Power Broker.”

8. The Swimmers by Julie Otsuka: I love when artists take unexpected risks that allow them to bring fresh perspective to a story. Otsuka opens “The Swimmers” in first-person plural, describing a group of people who show up at a pool every day to get their exercise. It’s a bold choice that drew me in, making me wonder where she would take this greek-chorus-like narration. “Most days, at the pool, we are able to leave our troubles on land behind … And for a brief interlude we are at home in the world. Bad moods lift, tics disappear, memories reawaken, migraines dissolve, and slowly, slowly, the chatter in our minds begins to subside as stroke after stroke, length after length, we swim. And when we are finished with our laps we hoist ourselves up out of the pool, dripping and refreshed, our equilibrium restored, ready to face another day on land.” When a crack opens in the pool (a metaphor that could stand for so many things), that chorus is broken up, the swimmers thrown out of their regular community, and Otsuka shifts to the story of one of the women, Alice, and her battles with dementia– another challenging narrative choice. A beautifully written story about love and community and mothers and daughters from a major talent.

9. Why We’re Polarized by Ezra Klein: No, it hasn’t always been this bad. In fact, some fifty years ago, our political parties hosted a range of ideologies that forced them to work out compromise before bringing issues to the other party. The duopoly made a conscious decision to gain more alignment and ideological integrity; we’re all paying the price. Klein illuminates The Big Sort and offers some prescriptions to move us toward more informed and intelligent debate. Seems like the toothpaste is out of the tube, but coupled with The Fourth Turning, I’m left believing (hoping?) that this too shall pass. I’m also left understanding that the individuals who make up the system are acting rationally in accordance with current incentives, which in aggregate creates this dysfunctional system. While this doesn’t make the fix easy and might seem like small consolation, it does help me empathize with people that are easy to characterize as inept, evil or both.

10. Memphis by Tara Stringfellow: An aspiring artist lives in the tension between a family’s (and city’s and country’s) troubled past and the possibility of a brighter future. Stringfellow tells a multi-generational, many-layered story of women in Memphis trying to thrive and survive. They’ve fled dangerous situations, harbored secrets, cried alone, and relied on one another. “Memphis” is both a title and a character, a place at the heart of the Civil Rights movement where we’ve seen progress and stagnation, hope and heartbreak. A powerful debut novel exploring those same themes.

Some more great reads:

Also a Poet: Frank O’Hara, My Father, and Me by Ada Calhoun: A woman sets out to finish the biography her father never could in this thoughtful memoir that explores friendship, fathers and daughters, and the nature of art.

Crook Manifesto by Colson Whitehead: The second book in Whitehead’s trilogy about New York City and a cast of characters trying to make their way amidst its chaotic underworld and all its machinations.

Good Talk: A Memoir in Conversations by Mira Jacob: A mom talks to her son about growing up as a person of color in today’s America in this remarkable graphic novel.

If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English by Noor Naga: A romance novel (of sorts) that turns that convention on its head, exploring what it means for someone to return to a homeland that isn’t really theirs.

In Love by Amy Bloom: A writer tells the story of her husband’s assisted suicide decision after he gets his Alzheimer’s diagnosis. Deeply touching.

Power and Prediction: The Disruptive Economics of Artificial Intelligence by Jay Agrawal, Joshua Gans, and Avi Goldfarb: Most artificial intelligence books are out of date by the time they’re published. This one (a follow-up to “Prediction Machines”) looks at the technology and its impact through an economic lens.

The Creative Act: A Way of Being by Rick Rubin: A call for everyone to embrace their artist self– much needed as we must claim agency over the generative powers of AI.

The Escape Artist: The Man Who Broke Out of Auschwitz to Warn the World by Jonathan Freedland: In April of 1944, Rudolph Vrba managed to escape almost certain death and set out to warn the world about Nazi atrocities only to find few would believe him.

The Sentence by Louise Erdrich: A ghost story of sorts that turns out to be a love letter to independent bookstores from one of our greatest writers.

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O’Neil: O’Neil exposes the dangers of deploying more and more algorithms at scale, a reality that already informs so much of our existence.

Wellness by Nathan Hill: “Wellness” wonderfully satirizes so much about our current world while not presenting the characters as caricatures or delivering a bunch of cliche, moralizing lessons. Thought-provoking about art, love, and how our pasts shape our present and future.