What George from Modesto and Joe from West Chester County Can Teach Us About AI, the Future of Work, and Making Sense of Our Career Journey

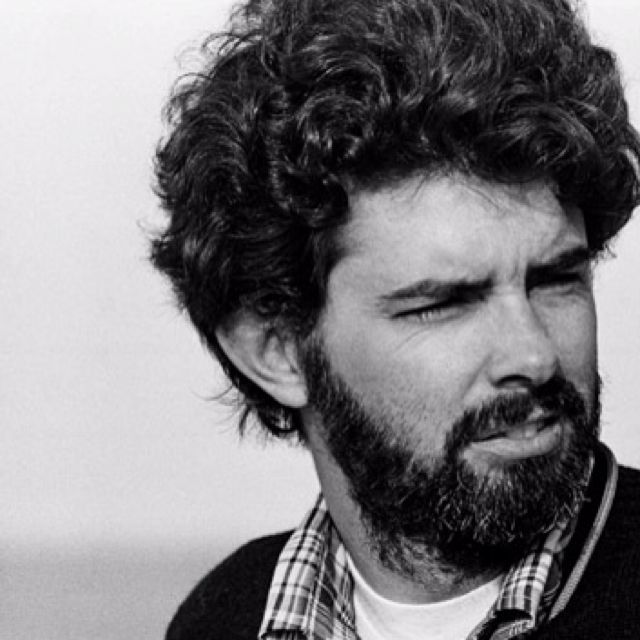

In 1967, at the height of the Vietnam war, George, a recent college graduate from Modesto, CA, tried to join the United States Air Force. The Air Force turned him down. Too many speeding tickets. He was later drafted into the Army, but medical tests showed he was diabetic, a diagnosis that exempted him from combat.

A man who would go on to leave an indelible mark on the world hardly appeared destined for greatness.

But we know some heroes don’t wear capes.

And some heroes don’t have a grand life plan.

Some heroes teach us about heroes.

And apparently some heroes who teach us about heroes like to drive fast.

#

I leaned back in my chair, shrinking from the brouhaha that was breaking out in the middle of the room, happy to be on the periphery. At the top of my page, I had written: “Y2K IT Priorities.”

People talked over one another, voices growing louder. Twelve seats at the table. Twenty-two of us in the room.

“Don’t you understand how important this is?” A fist pounded on the table. “It’s not optional.”

“If they get their req thing, we need our onboading solution.” Another loud voice.

I wrote “TRAINWRECK” beneath the heading and then jotted down some thoughts to improve the process.

Need clear prioritization criteria. Strategic alignment? ROI? Level of difficulty? Change readiness? Something more than fist-pounding. We need a process. Some artifacts and clearer role definition.

I’d type up my notes after the meeting, paste them into an email, and send them to my boss. From there, it would be out of my hands. People above my paygrade would consider how we might “reengineer this process.” That was the language of the late 90s. It was likely too late to salvage the 2000 planning cycle, but maybe my notes would make a difference come 2001.

Another shouting match broke out. One voice rose above the din. “We’re a billion dollar company and we don’t know how many reqs we have. We’re like a factory who knows how much product we shipped but doesn’t know how many orders we received. Does that make sense to any of you?”

The speaker scanned the room for agreement. My pulse quickened. My breath shallowed. I looked down at my notebook. Tried to melt into my chair, which was pressed against the back wall. I jotted on my paper. “Simple, stream-lined business case template.”

Yeah, 2001 would be a lot better than 2000.

#

We’re told to be the heroes of our own story. Easier said than done. Our natural tendency is to avoid conflict. Who wants to rock the boat? And right now, everything’s so confusing. It would be hard to know if we’re even rocking the right boat.

With AI casting a shadow over long-term employment prospects, the way forward has never been murkier. We’re left pressing our chair against the wall, scribbling some notes, or doomscrolling some social media app, waiting for clarity. Hoping it will all be clearer and better next year.

The experts fill the void with sound and fury, but what does it signify? How do we separate signal from noise? We’re either headed for a world of frictionless abundance or some dystopian future. In both cases, AI strips us of agency. It’s coming for our jobs. Maybe all jobs. It will take our paychecks and our dignity. Run roughshod over our economy. We’re the objects of sentences, stuck in this liminal space.

We wait for answers. For the next shoe to fall.

Passively waiting for the heroes to make it happen.

Waiting for companies to make announcements.

Waiting for Silicon Valley to unleash its next LLM.

Waiting for the government to establish reasonable guardrails.

Waiting for someone to spell out the retraining plan or clarify the “safe” jobs.

Waiting for Artificial General Intelligence to have been achieved.

Waiting for something we can’t even fathom because all this stuff is over our head.

Heroes, whether they’re dressed in spandex or not, can’t afford to wait. They answer the call. They are ordinary people who rise to the challenge and do extraordinary things. They don’t shy away from conflict. At least not forever.

That’s what George from Modesto taught us, and I guess that’s what I’ve learned… even if I didn’t realize it at the time.

#

Stymied in his attempts to serve his country, George from Modesto returned to the University of Southern California to pursue graduate studies in film making. A few years later, he met up with director Francis Ford Coppola, who asked him to write a coming-of-age screenplay. George’s script, loosely based on his Modesto childhood, was turned down by every major studio save one. Universal Pictures bankrolled the film, and it proved to be a commercial and critical success.

With American Graffiti under his belt, George was emboldened to write another script. He turned his attention to his childhood love of science fiction. After failing to obtain the rights to comic book character Flash Gordon, he decided he’d write an original adventure story set in space. On April 17, 1973, George Lucas wrote a 13-page treatment called The Star Wars based loosely on a 1958 Akira Kurosawa film The Hidden Fortress.

Lucas considered his work more informed by the fairy tales of old than futuristic science fiction. He was interested in mythology and picked up a 25-year-old book by a guy named Joseph Campbell. “It was very eerie because in reading The Hero with a Thousand Faces I began to realize that my first draft of Star Wars was following classic motifs… So I modified my next draft according to what I’d been learning about classical motifs and made it a little bit more consistent.”

The rest, as they say, is history. The Star Wars franchise has taken in more than $10 billion at the box office alone, never mind happy meal toys, trading cards, light sabers, Darth Vader yoga mats, Star Wars-themed adult diapers, and Jar Jar Binks candy tongue. Lucas figured out a story structure that resonated with a basic human desire for meaning and transcendence, and he figured it out from reading Campbell.

#

What does this have to do with AI and jobs?

We can’t all write Star Wars. We can’t all sell movie-themed adult diapers. We can’t all be George from Modesto.

Doesn’t someone still need to spell out the way forward?

But heroes don’t see the way forward. They make the way forward. They answer the call.

Often, they’ve refused “the call” again and again. Finally, someone or something presses them into action.

#

I think back to that 1999 prioritization meeting. I literally did not have a “seat at the table,” and I was more than okay with that. I had pulled in my chair from some cubes outside of that conference room. My position existed because we, like most fast-growing companies, were light on process—more likely to reference a six-pack than six-sigma. I was hired onto a team that mapped future-state processes so that the company could implement an Enterprise Resource Planning tool. This meeting masquerading as a pro-wrestling match occurred shortly after my thirtieth birthday.

I had wandered through my twenties with no discernible career direction. With English and Philosophy degrees to my name, I worked in a group home outside of Cleveland, taught Freshman composition in Philadelphia, wrote proposals for an environmental company in Syracuse, and then finally took a job as a business process modeler (whatever that meant) for a Baltimore-based staffing company.

I didn’t know what I wanted to do, but I had come to a few realizations: I didn’t want to work for a big company; I didn’t see myself as part of “corporate America;” and I didn’t really care to be in a leadership role. I preferred to be behind-the scenes. I was social, but it took me a while to feel confident in new social settings, and I didn’t see work as a place to make friends.

All of this might have been well and good, but I also realized that rent doesn’t pay itself, so I took jobs to pay the bills and buy time while I figured out what I wanted to do.

This meeting happened a few years into my process-modeler tenure, and I liked this company. Its culture had disabused me of some of my notions of what “corporate America” meant. People were competitive, but they didn’t have sharp elbows. There was a spirit of collaboration and a commitment to development that suggested those around me genuinely wanted me to get better. We were building something, and there was a shared sense of mission.

I still considered myself someone better seen than heard– the guy with the glasses who brought his laptop to meetings when the charismatic sales leaders often didn’t bring a pen and paper. The guy perfectly willing to sit back while those sales leaders offered their opinions.

The Y2K technology planning meeting had no chance of getting on the rails. The four operating companies competed with one another to be louder and more passionate, and then they’d team up to question why the shared service couldn’t just find a way to get all this stuff done. I was taking copious notes and bulleting out process improvements. We were prioritizing based on emotion and rhetoric and rewarding the fist-pounding. We could do better. Beyond that, there was a lot of overlap in the asks, but each business called their request something different and wanted to focus on the functionality they perceived to be unique to their request as opposed to all that was common.

Thirty minutes into the meeting, everyone knew it would end in frustration. Odds were good that someone would be storming out. I was hyper-focused on capturing the challenges and identifying a “should be” process when I saw a flip-chart marker roll in front of my chair. I looked to my left and realized my boss Tony must have dropped it. I couldn’t quite reach it without getting up, so I did my best to grab the marker without drawing undue attention. When I turned to give it back to Tony, I saw him push my chair out into the hallway.

In that moment, all air had been sucked out of the room, everything was in slow-motion, and someone had cranked up the heat.

“Andy, I know you’ve been taking some notes,” Tony said. “Why don’t you share what you’re thinking and help us land this plane?”

Forty-two eyes were on me, the only person standing. I held the marker and glanced at two flip charts in the corner.

I started to speak a few different times, but only random syllables came out. “I don’t know that I have any answers,” I finally managed to say while I turned various shades of red. I could feel the sweat coming through my shirt. “I mean, I’m just, I don’t know, I’m making some notes.”

“This couldn’t get any worse,” said one of the CFOs. “Help us out.”

I couldn’t breathe.

#

Not unlike Lucas, Joe from West Chester County took a meandering path to his now-seminal theories. In 1921, Joseph Campbell enrolled at Dartmouth only to transfer to Columbia where he studied English Literature. He stayed on at Columbia and pursued a master’s in Medieval Literature, which he completed in 1927. From there, he earned a fellowship that allowed him to study Sanskrit and Old French in Europe. When he returned from Europe, though, he couldn’t get faculty approval for further study, so he dropped out of Columbia.

Campbell was not deterred. The country was in the early days of the Great Depression. He spent the next five years holed up in a rented bungalow following his curiosity. He broke his days into three four-hour segments, committing two of those segments to intense reading as part of his independent study. Maybe the faculty at Columbia wouldn’t sponsor him, but he had some ideas about the underpinnings of narrative and how they served to give our lives meaning. You’d better believe he was going to flesh out those ideas.

While most before him had studied difference, Campbell saw commonality. He went so far as to propose that all mythic narratives have the same elements and are all variations on a single story, something he called the Monomyth. It took him the better part of two decades to publish his theory in the book George Lucas would later read. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), Campbell defines the Hero’s Adventure: “The hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

Campbell further detailed the structure of this journey into the unknown world, describing archetypal characters and the “everyman” who needed to square off against shadows, defeat the dark side, and return to the known world in possession of a magic elixir, transcendental wisdom that would set society free.

After Lucas re-wrote Star Wars in accord with the Journey, Campbell’s work experienced a renaissance. Every screenwriter became an expert on The Hero’s Journey. Critics viewed recent box office successes through its lens: Rocky wasn’t just the story of a kid from Philly boxing for the heavyweight title; it was about a down-on-his-luck leg breaker thrust into the spotlight who discovered that that true fulfillment had more to do with Adrian’s love than winning the heavyweight title. The Hero’s Journey informed the next set of blockbusters: archaeologist Indiana Jones raced the Nazis to find the Ark of the Covenant, a face-melting artifact with untold spiritual significance.

To this day, most screenwriting courses and most screenplays follow Campbell’s journey.

#

I don’t remember much of the 25 minutes after I stood in front of the room sweating through my shirt. I could blame time’s passage—it has been more than a quarter of a century—but I didn’t remember much a few minutes after the meeting. I probably alternated between sharing my thoughts and asking questions– tried to get them to see where there was agreement and scribbled a few things on a flip chart labeled “Parking Lot” when we veered off into unproductive territory.

No one stormed out, but no one left feeling great. Especially me. I wrapped the meeting by citing the couple of things we had agreed on and running through a list of actions and open items. People nodded reluctantly and acknowledged there was more work to do.

No one left the room feeling good about the experience, especially me.

I went straight to Tony’s office, ready to tell him what I thought and wondering whether I’d quit or be fired. I let him know how unfair that was. He shouldn’t have put me in that position. This wasn’t my job. It didn’t play to my strengths.

He laughed, which only stoked my frustration.

“I’m glad you think this is funny,” I said.

“I think it’s hilarious,” he said.

“I think it’s totally inappropriate. I think you should think more about how you made me feel.” I didn’t shrink from the conflict. He needed to know.

“Let me ask you something,” he said. “How was the meeting going before I pulled your chair away?”

“It was a disaster.”

“Give it a grade.”

“F. I mean, we were getting nowhere.”

“And how about after?”

“It was a disaster,” I said.

“Give it a grade.”

“D.”

He laughed again. “You’re a tough grader. Even so, last I checked, a D is better than an F.”

“I don’t know. I might take the F if I don’t have to sweat through my shirt.” I found myself smiling. I couldn’t help it. His responses had disarmed me. Maybe I wouldn’t quit, but this couldn’t happen again.

And that’s when he shifted to serious. “Look,” he said. “This company is doing something special. But we’re going to hit a wall, and the only way we get through that wall is if people step out of their comfort zone.”

As he talked, I thought about my rebuttal. How I wasn’t the one to take those risks. He hired me to be an analyst. Seen but not heard.

“And I know you can do a lot more than we’re asking you to do. In fact, I need you… No. We need you to take on much more responsibility. You see things that they don’t. That I don’t. We need you to start leading differently.”

He didn’t use these words, but that’s the day that I realized sometimes different is better than better. This wasn’t about my smarts or some innate talent I brought to the company. I just looked at the world differently. Maybe it was my English major training. Or my philosophy degree. When they fought for features, I looked for patterns. When they shouted answers, I asked questions. Maybe my time in the group home had developed some empathy muscles. Maybe my time teaching had prepared me to facilitate a tough meeting.

I had felt intimidated by the charisma of the sales-focused extroverts. In that moment, I felt complementary. Even needed.

I had walked into Tony’s office feeling small and less than. I was ready to quit. Nothing about the experience had changed, but Tony reframed the opportunity. Believed in me much more than I had believed in myself. I walked out of the room ten-feet tall and ready to conquer the world. Or at least bring those twenty-one other people back together to ensure we made some tough decisions. I drove home that day with confidence and a sense of mission.

Every day after that, I subscribed to that mission. My job became grabbing that marker when it was in front of me, getting comfortable being uncomfortable and tapping into the wisdom of the room. And over time, it also involved pulling the chair away from other people who had more to give. People who felt constrained by their title or who limited themselves with their self-talk.

#

What should we take from Lucas and Campbell’s stories? How does the monomyth apply to work and life in 2025?

We’re being called into an unknown world, with AI rewriting the rules of work and creative destruction happening in shorter and shorter cycles. The future has never been more promising and less clear.

We’re told the heroes are in Silicon Valley, but we are the ones who must step across the threshold into this unknown world.

Heroes answer the call. Sometimes reluctantly. Sometimes when they don’t even realize it.

They likely won’t follow a prescribed path. They don’t have some master plan because the changing world renders most long-term plans obsolete.

They’ll follow their curiosity and have to navigate a new, unpaved path. At times, they’ll feel like they’re lost in a dark, thick forest. Campbell told us that’s how we would feel.

Through it all, they must retain their agency. They’ll wonder “why me?”, and they’ll acknowledge that they’re just ordinary people trying to make a difference.

Sometimes, the Dark Side gains advantage. Sometimes it appears the Dark Side will win.

Through their persistence, though, heroes find a way.

Their ultimate success will not be about earning more or some explicit reward. They will discover timeless wisdom and do their best to share it with humanity (“boons for fellow man”).

That’s when the Hero’s Journey will be complete.

Until the next call.

#

I don’t mean to imply that I’m some kind of hero– that my story belongs in the same breath (or even essay) as George from Modesto or Joe from West Chester County.

I don’t have delusions of grandeur. I don’t for a minute think I fended off the dark side and somehow changed the world. Or brought back some wisdom that will shape the way people derive meaning from their own stories for years to come.

In fact, on many days, I felt anything but heroic. Too many times to count, I felt lost or inadequate. I wondered if my actions were aligned with some greater mission at all. If we were all just going through the motions. There were days when I drove home saying The Serenity Prayer, feeling ineffectual. Nights when I woke up, grinding my teeth and wondering why I hadn’t acted differently that day. Or I wondered if I’d have the courage or wherewithal to solve a particularly thorny problem.

I’m fairly confident Superman and Wonder Woman didn’t give themselves ulcers.

No, I definitively wouldn’t qualify as a hero.

But then again, Campbell and Lucas weren’t talking about Superman or Wonder Woman. They posited that heroes are ordinary people who answer the call. They changed the connotation and broadened the definition. Their heroes grind their teeth and wonder whether they’re really making a difference. Their heroes fret and worry and sometimes say The Serenity Prayer.

When asked what business we were in, we’d often say, the Leadership Development Business. We realized that our growth, our ability to fulfill our purpose, was constrained and enabled by our ability to develop leaders.

When I think about Campbell’s definition, I realize that I’ve spent most of my life working with genuine heroes. Another name for a leadership development business could be the hero development business. For all their struggles, heroes understand that their job is to fulfill their potential, and they understand that their job is to help others see potential they might not have seen in themselves.

Campbell’s heroes pick up markers and sweat through their shirt. They also pull chairs into the hallway and tell people they believe in them. I realized that I didn’t need to have all the answers. No, I just needed to realize that I was surrounded by heroes, and that my job was to help them answer the call. My job was to amplify their voices and ensure we stayed true to a broader mission. I realized that the more I believed in those around me, the more I believed in myself.

I’ve been so fortunate to work with so many people who struggled and believed and persevered and recognized they could do more and be more. I’ve been so fortunate to work with so many heroes.

Right now, the world needs heroes. Not Wonder Woman and not Superman. Everyday heroes like the ones George and Joe taught us about.

#

Sometimes heroes read LinkedIn articles.

Sometimes they come across a quote that reminds them to retain their agency and answer the call. Joseph Campbell offers up one such quote: “The hero journey is inside of you; tear off the veils and open the mystery of your self.”

The time is now. No one is coming to rescue you. You are the hero of your story. The journey is inside of you. Take it from George and Joe (and me).

It’s time to pick up the marker.

It’s time to answer the call.

Let’s go.